CONRAD GESSNER

NOMENCLATOR AQUATILIUM ANIMANTIUM, 1560

THE TIDY AQUARIUM

Conrad Gessner's "Nomenclator aquatilium animantium", which translates as "Nomenclature of the Aquatic Animals", appeared in 1560 as a handy revision of his fourth "Animal Book", the Latin fish book.

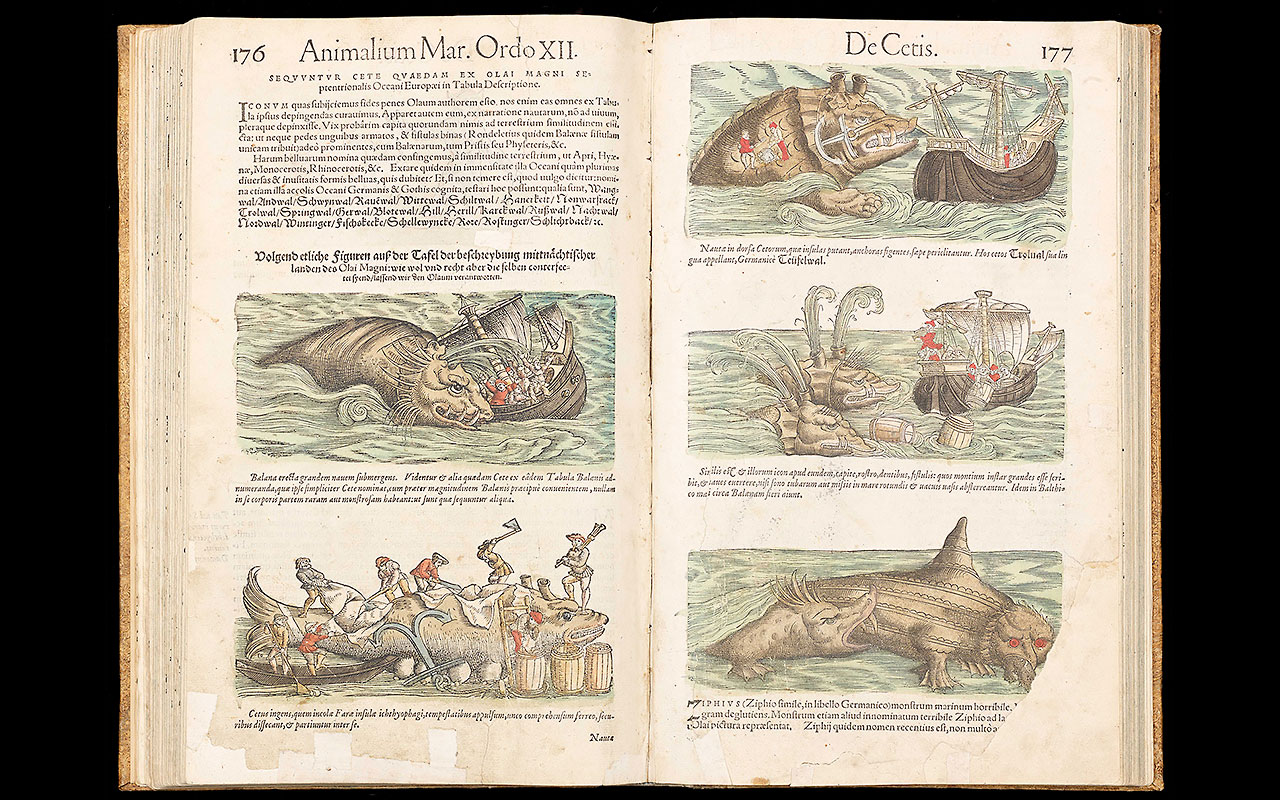

Whereas Gessner describes the animals in alphabetical order in the other animal books, he proceeds with the nomenclature systematically in the fish book. He distinguishes marine animals from freshwater animals and presents classifications based primarily on the outward appearance of the animals. Monsters known from adventure reports and images are also included. Animals which live both in the water and on land are mentioned at the end of the book.

Each treatise starts by naming the animal in different languages. This is followed by descriptions of its way of life, external appearance, and character. Finally, Gessner addresses its use as food or medicine. Each water animal features on a woodcut, which is probably one of the main reasons that the animal books and nomenclature were so popular. Only a few of the images were done by Gessner himself. Gessner thanks the numerous scholars from all over Europe who sent him drawings and descriptions in the foreword.

THE HELPFUL NETWORK

Gessner had only drawn some sea fish after personal observation during a study trip to Montpellier in 1540, and to Venice in the summer of 1543. He therefore worked mainly from his desk. He relied on around 500 publications to be able to describe sea dwellers. Gessner also sent a search list with animal names to his scholarly network in 1548. As soon as a description came in, the corresponding animal name received a little star.

The medical professor Guillaume Rondelet made his work "Libri de piscibus marinis" (1554/1555) available to Gessner for the fish book, and Gessner used about 80% of the woodcuts in his own book. Gessner also took numerous illustrations from the work "De Aquatilibus", which was compiled by the naturalist and physician Pierre Belon (1553). Gessner was guided by Rondelet's and Belon's works in his texts, too.

But Gessner not only gathered descriptions and images but also real animals which his network sent him, sometimes from distant lands. Gessner called the resulting cabinet of curiosities his "Museum".

CITY PHYSICIAN OR NATURALIST?

Conrad Gessner came from a poor family. His owed his career to the support of Zwingli and his student Heinrich Bullinger. However, after an early marriage to Barbara Singysen, he had to interrupt his studies and work as a teacher. After further petitions, he was allowed to study medicine in Basel, which he then interrupted for a professorship in Greek in Lausanne in 1537. In autumn 1540, he returned to Basel for a few months to complete his studies. Finally, Gessner gave lectures at the Carolinum in Zurich and published the "Bibliotheca universalis" in 1545, one of the first printed bibliographies.

After the death of Zurich's city physician in 1552, Gessner was the only academic doctor to apply for the coveted position. He was rejected by his sponsor Bullinger, of all people, with the words: "But the very famous Dr Conrad Gessner would rather give lectures and pursue his scientific publications than listen to the complaints of the ill." The position first went to the surgeon Jacob Ruff. Gessner was not named city physician until two years later. Since Ruff retained nearly all of his duties as city physician, Gessner still had time to do his own research. During this time, he produced the animal books and the nomenclature.

In 1558, the city council promoted him to Canonicus and increased his income. Gessner added an upper floor to his house and had its 15 glass windows painted with water animals. He died there from the plague in 1565.

A PANOPTICON OF ANIMALS

Gessner became famous through his natural history and linguistic works, but primarily through his animal books, the "Historia animalium". He wanted to capture the "immeasurable realm of creation" as completely as possible in word and image with this multi-volume work. Following Aristotle, Gessner divides all living creatures into six main groups: Live-birthing quadrupeds, egg-laying quadrupeds, birds, aquatic animals, snakes and insects.

In contrast to natural scientists like Pierre Belon, Gessner also describes animals that we call fantasy creatures today. Gessner copied a multitude of these fantastic water creatures from the Carta Marina by Olaus Magnus, an early map of Northern Europe. Although he partly doubted their existence himself, he included them in his encyclopaedia nevertheless.

The nomenclature is particularly significant because it names animals in different European languages. Gessner's neologisms were adopted in many cases, which meant they had a lasting impact on zoological nomenclature.